What binds Riyadh to Rawalpindi may borrow a nuclear umbrella, but its shadow stretches from Washington to New Delhi, and for India, it is not just a warning to prepare, but an invitation to lead.

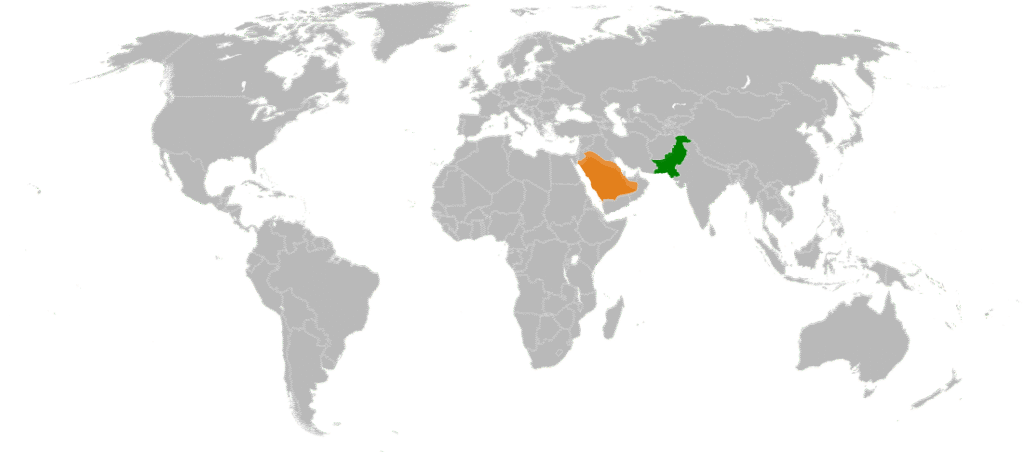

When Pakistan and Saudi Arabia signed their “Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement” in Riyadh on 17 September 2025, the symbolism was unmistakable. Inked at Al Yamamah Palace by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the pact pledged that aggression against one would be treated as aggression against both. To some, this was an affirmation of an already close partnership. To others — in New Delhi, Tehran, Washington, and Brussels — it signalled the opening of a new chapter in global security politics.

More than a bilateral pact, the agreement binds together South Asia and West Asia’s security architectures, introduces nuclear ambiguities, and unsettles a fragile balance of power stretching from the Gulf to the Himalayas.

Saudi Arabia’s move reflects a long-term quest for strategic autonomy. For decades, Riyadh relied on U.S. security guarantees. But American hesitancy during the Gaza war, its chaotic retreat from Afghanistan, and a broader inward turn have left the Kingdom searching for new anchors.

Pakistan offers three things: manpower, credibility, and nuclear deterrence. Saudi Arabia has repeatedly hinted it will not sit idle if Iran crosses the nuclear threshold. By aligning with Islamabad, Riyadh secures a political hedge, a shield it can invoke without incurring the financial or diplomatic cost of building its own bomb.

For Pakistan, the pact is a lifeline. Domestically, it is reeling under economic crisis, climate disasters, and IMF-dependence. Diplomatically, it has been relegated to the margins of global politics. A formal security pact with Riyadh restores prestige and relevance, elevating Islamabad beyond its usual India-centric framing.

Material benefits are immediate. Saudi aid, investments, and remittances are critical for Pakistan’s survival. By presenting itself as Riyadh’s security partner, Islamabad converts dependency into leverage. Yet risks abound. A future Middle Eastern conflict could drag Pakistan into wars far beyond its borders, stretching an already strained military. But the costs for Pakistan may also be internal. Aligning too closely with Riyadh risks aggravating sectarian tensions at home, where Shia communities have long been wary of Pakistan serving as a Saudi proxy against Iran. The pact could deepen domestic divides, invite retaliatory violence from extremist groups, and further tilt power towards the military establishment in Rawalpindi at the expense of civilian institutions. If Pakistan is drawn into Gulf rivalries, the blowback may be felt as much in Karachi and Quetta as in Riyadh or Tehran.

India’s response must go beyond caution. This is a moment to lead, not just adapt.

One element is diplomatic leadership. India can convene Gulf–South Asia dialogues on energy security, migration, and maritime safety. Its diaspora is not only a vulnerability but also a bridge, offering cultural and political capital that New Delhi can deploy as soft power.

Another priority is strategic reassurance. By intensifying ties with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, India can demonstrate that it remains a partner of first choice in the Gulf, capable of balancing security with economic growth.

Equally important is global norm-building. India can use its standing in the UN, BRICS, and G20 to spearhead efforts against nuclear outsourcing, positioning itself as a guardian of responsible nuclear conduct in an era of proliferating risks.

Finally, there is the maritime vision. Expanding naval deployments and securing basing access in Oman, East Africa, and Southeast Asia will allow India to project itself as a guardian of sea lanes that connect the Gulf to Asia and beyond.

Taken together, these initiatives mean India can use the Rawalpindi–Riyadh accord not merely as a challenge to manage, but as a catalyst to cement its role as a system-balancer between the Gulf, Asia, and the wider world.

Yet India’s role must not be confined to damage control. This is also a moment for New Delhi to project leadership as an economic powerhouse, democracy, and responsible nuclear actor with credibility in both the West and the Global South.

A central concern for Washington is the nuclear dilemma. For decades, the United States has resisted Saudi Arabia’s efforts to acquire nuclear capabilities. The prospect of a Pakistani deterrence “extension” undermines U.S. non-proliferation diplomacy and risks setting a dangerous precedent for other allies who might now be tempted to shop for external nuclear guarantees.

Compounding this challenge is Pakistan’s strategic shift. Once a frontline U.S. ally during the Cold War and the “war on terror,” Islamabad today is aligned more closely with China and bankrolled by Gulf partners. The Saudi–Pakistan pact underscores Washington’s shrinking leverage, where U.S. military aid has been supplanted by Saudi capital and Chinese investment.

Finally, there is the issue of Indo-Pacific overlap. The agreement forces the United States to acknowledge that Gulf stability and South Asian deterrence are increasingly intertwined. India, already at the heart of Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy, now emerges as an even more crucial partner in shaping Gulf security and reinforcing global non-proliferation norms.

For America, then, the pact is a reminder of declining primacy, but also of the need to double down on India as a stabilizing anchor across the Indo-Pacific and Gulf.Europe shares the unease. Brussels sees three risks:

- Erosion of the NPT regime, as nuclear umbrellas cross regions.

- Energy instability, if Gulf tensions escalate into conflict.

- Intelligence gaps, if Riyadh begins relying more on Pakistan than on Western partners.

But both the U.S. and EU face a dilemma: confront Saudi Arabia and risk alienating a key energy supplier, or accept ambiguity and hope the pact remains more symbolic than operational.

The rest of the Gulf, too, is watching carefully. The UAE, which has cultivated its own defence partnerships with both India and the West, may view Pakistan’s new role with quiet unease, wary of being sidelined in Riyadh’s security calculus. Smaller Gulf monarchies such as Kuwait, Bahrain, and Oman, traditionally cautious in foreign entanglements, may fear being dragged into a Saudi-driven alignment with Islamabad that complicates their own balancing acts with Iran. Rather than cementing Gulf unity, the pact could subtly strain the cohesion of the GCC, with each state recalibrating how closely it wants to follow Riyadh’s lead.

Beijing gains the most without lifting a finger. Both Pakistan and Saudi Arabia are central to China’s Belt and Road vision: Pakistan through the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, Saudi Arabia through energy and infrastructure partnerships. A defence compact between two of Beijing’s closest partners reduces U.S. leverage and aligns with China’s preference for a non-Western security architecture.

If Riyadh–Rawalpindi security ties deepen, Beijing could emerge as the quiet guarantor of this axis, linking South Asia and West Asia under its expanding influence, further narrowing India’s strategic room for manoeuvre.

For Moscow, the arrangement is another crack in Western influence. With its deepening ties to Riyadh through OPEC+ and energy diplomacy, Russia benefits when Saudi Arabia diversifies its partnerships. Islamabad’s alignment with Riyadh indirectly strengthens Moscow’s argument for a multipolar order and creates new opportunities for arms sales and diplomatic outreach.

For Iran, the Riyadh–Islamabad alignment is a stark reminder of its vulnerability. Despite the Chinese-brokered détente with Riyadh in 2023, Tehran will view the deal as a hedge against itself. That may accelerate its missile program, deepen ties with non-state allies in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, and strain the fragile balance with Saudi Arabia.

Israel, too, faces unease. While it has quietly deepened cooperation with Riyadh in recent years, the idea of a Pakistani nuclear umbrella introduces a new nuclear actor into Gulf dynamics. This complicates Israel’s own strategy on Iran and injects new uncertainty into potential Saudi–Israeli normalization.

The pact reflects the realities of today’s multipolar order. Unlike the Cold War’s binary blocs or the post-1991 U.S. unipolarity, today’s world is fragmented. Saudi Arabia seeks autonomy, Pakistan seeks relevance, China and Russia seek leverage, and the West seeks to manage decline. Alliances are fluid, transactional, and often contradictory.

The Riyadh–Rawalpindi pact exemplifies this: the Kingdom remains a major U.S. arms buyer, hosts Western troops, partners with China economically, coordinates oil policy with Russia, and now secures defence guarantees from Pakistan. In such a world, ambiguity is strategy.

What makes the Saudi–Pakistan defence pact more consequential than a routine agreement is the way it fuses the security dynamics of South Asia and West Asia. Until now, these theatres were often analysed separately: the Gulf as an energy hub shaped by U.S.–Iran rivalries, and South Asia as a nuclear flashpoint defined by India–Pakistan tensions. By binding Riyadh to Rawalpindi, the two regions have been stitched into a single strategic fabric. For India, this means the Gulf can no longer be treated as a compartmentalised partner defined only by oil, trade, or diaspora ties. It is now part of its extended security neighbourhood, one where maritime routes, nuclear norms, and great-power rivalry converge.

This defence arrangement is not simply a regional compact; it is a microcosm of global complexity. For India, it poses risks to security, diaspora, and energy, but also offers an opening to lead. In an age of borrowed umbrellas and shifting sands, India’s strength will lie not in merely navigating the waves, but in piloting the ship.